HOW MUCH SEX DO F1 DRIVERS GET?

Let's just say Formula One is not as clean cut as it likes to pretend.

Formula One drivers were once the undisputed playboys of the sporting world, with off-track exploits to rival anything they did behind the wheel. But today’s breed are a much tamer bunch – or are they? As a paddock insider for the past 20 years, allow me to dish the dirt on the men who live at 200mph.

Despite their high-octane day job, the present generation of F1 drivers are often compared unfavourably to their predecessors in the rock n’ roll lifestyle stakes. But while the anecdotes of excess may be in shorter supply, are the current crop really behaving any better? In previous eras – and the one everyone seems to look back on most rosily is the 1970s – every driver wore rebel colours. Back then, sex was safe and racing was dangerous. They were all barking mad, oversexed and privileged. Because their life expectancy was so short, they wanted to pack as much fun in as they could. Consequences were never considered.

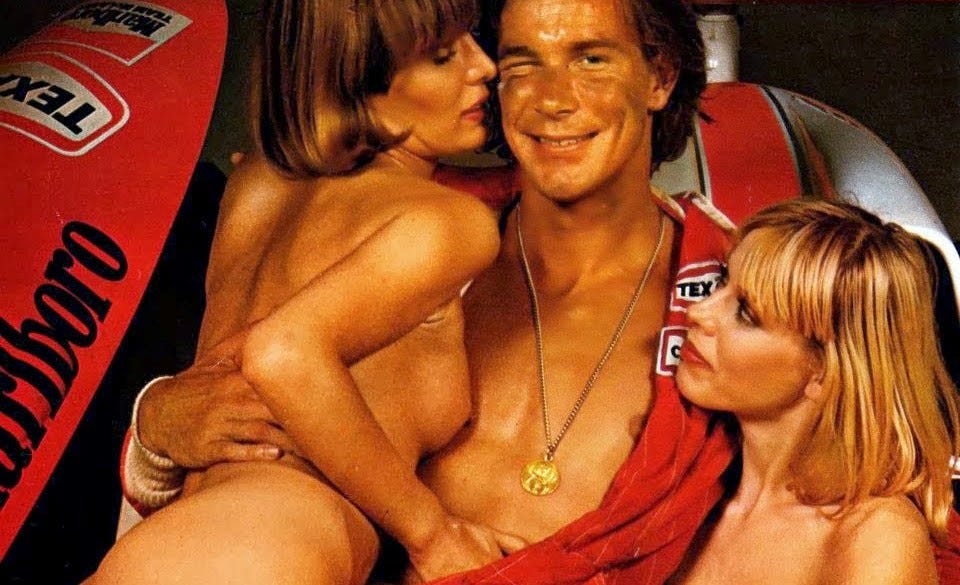

The biggest tearaway was James Hunt who, legend has it, bedded 33 British Airways stewardesses at the Tokyo Hilton on the eve of winning the world championship. He raced with a badge sewn onto his overalls that read: Sex, the breakfast of champions. He was also almost permanently under the influence of booze, cannabis and cocaine, and this began to affect his driving.

Then there’s Alain Prost, who blames losing the 1984 world championship to Niki Lauda because Prost was up all night before a key race seeing to the needs of Princess Stephanie of Monaco.

Indeed, of all the great F1 drivers of that era, perhaps only Ayrton Senna could be held up as an upstanding role model. Senna was the first really professional driver who just focused on driving and fitness. That’s not to say he wasn’t glamorous – far from it. He had movie-star looks, palatial homes, helicopters, and a couple of high-profile girlfriends (including a romance with supermodel Carol Alt, who was married at the time), but none of that ever dented his ruthless obsession with winning. When groupies asked for his hotel room number, he gave them team-mate Gerhard Berger’s, who was justifiably grateful.

Back in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, even the sponsors were macho and dangerous. Mostly cigarette companies, they got into bed with motor racing because of the sex-appeal, danger and testosterone. But as the new millennium dawned, tobacco was forced out and banks, energy drinks and telecoms companies took their place. In short, it all became terribly clean cut.

I recall sitting a job interview in 2003 with McLaren’s PR and marketing chiefs. It came at around the same time a woman had sold her story to a tabloid about sharing a bubble bath with then McLaren driver David Coulthard. This, I told them, was the perfect image to promote their sponsors and that Mr Coulthard should receive some kind of bonus for his efforts. However, the team had been advised by their clients to try to contain all of DC’s playboy exploits. Whatever happened to ‘sex sells’, I wondered? Suffice to say, I didn’t get the job.

I blame Michael Schumacher. Sure, he’s an F1 legend (and, I hasten to add, we’re all rooting for his recovery), but his 91 wins and seven world championship titles are simply statistics. In the ‘90s he ushered in a new era of soulless, unsmiling corporate drivers that all but marked the end of the F1 playboy era. There’s a telling old Fry & Laurie sketch, loosely based on the German, in which Stephen Fry interviews a taciturn young racer. Growing increasingly frustrated with the driver’s lack of enthusiasm, the reporter eventually screams: “You do a job that half of mankind would kill to be able to do, and you can have sex with the other half as often as you like – I just need to know if this makes you happy?!”

The one time Schumacher did let his hair down, after winning his fifth title in Japan, he stole a forklift truck and threw a fridge through a window. My photographer friend James Moy managed to get the only photos, and sold them to the The Sun. The headline read: ‘Schu Trouble Macher’. Rather than tarnish his image it made him easier to relate to, more human.

But team PRs now insulate the media so that stories such as these – controversial and of a personal nature – don’t meet a wider audience. Sponsors are attracted to the youth, glitz and inherent risks of F1, yet are uncomfortable when it starts getting a bit too real.

Kimi Raikkonen first gained tabloid notoriety in January 2005 when he showed a London lap dancer the real reason he wore a six-point harness. Fuelled by vodka, I recall Kimi being caught in the ladies’ loos at a Red Bull party I attended in Shanghai that same year. His chaperones carried him back to his hotel and practically strapped him to the bed. They closed the door and walked down the corridor only to have their route blocked by a room service trolley bearing “20 Heinekens for Mr Raikkonen.”

These shenanigans look rather less laudable through the #MeToo prism (to which end, much-maligned Russian driver Nikita Mazepin caught serious flak in 2020 when he posted a video to Instagram of himself grabbing a woman’s breasts), but fans loved Kimi’s couldn’t-give-a-toss attitude. The Schumacher era had produced drivers who were robotic and, frankly, boring. We yearned for the characters of the ‘70s, like Hunt-the-Shunt. Kimi, too, was seduced by that period. He once entered a speedboat race dressed as a gorilla, so as to preserve his anonymity, and chose “James Hunt” as his nom de guerre.

Kimi, who finally retired from F1 at the end of 2021, loved driving but hated doing any kind of PR. This is obviously not ideal when there’s £100m worth of stickers on your car, but the lack of lip service was viewed as refreshing. Shrugged silence seemed to make him all the more magnetic.

Now, in the era of Netflix’s Drive to Survive (2019-present) drivers have been encouraged to come out of their shells more and express themselves as individuals. Team PRs will still blacklist journalists if they ask the drivers questions that aren’t suitably bland, but Netflix seems to get a pass. When the streamer cameras are rolling, perhaps in the knowledge the footage won’t be seen until the season is over, the drivers and their team bosses are far more vocal about whatever’s bugging them. Hallelujah. This is sport: you want to see anger, conflict and joy. It’s also fantasy: these guys are doing what every young man dreams of – racing cars, earning millions and getting their pick of the high-heeled trophies. But despite the less guarded approach under American owners Liberty Media when it comes to drivers speaking their minds, never do you hear about champagne-soaked ménage-a-trois aboard trackside yachts in Monte Carlo, which is a shame because they do happen.

Jenson Button came in for a lot of flak when he arrived in F1 in 2000. The 20-year-old purchased a yellow Ferrari 355, moved to Monaco, bought a yacht and traded up girlfriends. Too many distractions, warned the critics. Team principals didn’t take him seriously, thinking he lacked commitment. But when Button was finally given a winning car to drive, he was able to prove them wrong. On the eve of the 2009 Australian Grand Prix – his championship-winning season – in a display of his work ethic, Button went on a self-imposed sex ban with lingerie-model girlfriend Jessica Michibata ahead of the race. Half an hour after the chequered flag they made up for lost time in the Brawn GP hospitality unit. Interview opportunities were postponed.

The Button-bashing served as a warning to many of the youngsters coming through the ranks: Don’t be too flash. And if you must have a G450 and an island, try to keep it out of the papers.

Drivers these days start racing before they’ve hit double digits. They miss out on a normal childhood. Few emerge well-rounded. Lewis Hamilton is a prime example. The sport’s first driver of colour, he was signed to McLaren’s young driver programme at the tender age of 12, groomed to be a racing superstar from that moment on, with the media taking a strong interest.

A little while ago, as we drove around East London in the back of his chauffeured Maybach, I put it to Lewis that his upbringing was a bit like The Truman Show, under an intense public spotlight. “That’s a cool interpretation, it was a bit like that,” he agreed. “I was groomed and restricted and felt that was the only space I was allowed to be in.” He was surrounded by PR handlers, adhering to the corporates, and walking a press tightrope where they build you up then knock you down. He had to wear what he was told to wear, keep to the key messages, “look like this and behave like that,” and be, ultimately, who McLaren boss Ron Dennis – the man who a ten-year-old Lewis first approached at an awards dinner and pledged he’d race for one day – wanted him to be. It was the opportunity of a lifetime, no question, but it also restricted his personal development. It bound and clipped him like a bonsai tree, stunting his growth.

“For me, it was all about racing. I was generally quite shy as a kid”. So, it took everyone by surprise when in September 2012 Lewis announced he was leaving McLaren for Mercedes’ works team. “It was only then that I started to make my own decisions in life.” In the seasons that followed, this proved an absolutely inspired move. McLaren sunk into irrelevance (and are only returning to the top now, 12 years later). Mercedes, on the other hand, provided the car that would take Lewis to his second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh world titles. But, for me, the most striking thing about his rule at the three-pointed star was how he has blossomed as a character. “I started to take down some of the shields that had been put up around me.”

Lewis discovered who he was. “I’ve been finding out who I’m comfortable being,” he told me back in 2016. He has embraced his background, his future, and his off-track interests. He is out there living the life of a multimillionaire celebrity and he’s not afraid to show it. In the process he’s built a brand, he’s reached an audience that would never normally tune into motor racing but might to see him, and he’s annoyed jaded F1 purists who think racing drivers should stick to the Grand Prix Ball, rather than the Met Ball. The fact is Lewis doesn’t sleep. He has more energy and drive than the rest of the grid combined. He loves nothing more than proving people wrong.

Ultimately, it’s difficult to find a balance between pleasing the sponsors, appealing to the fans, and living your life. With the pressure that comes from having 700 staff and £200m of investment dependent on you, plus engineering meetings, press junkets, and demanding fitness regimes, you can’t go boozing and inviting girls back to your presidential suite till you’ve got the race out of the way – that is, unless you’re a test driver. The reserve racers have the best deal of all; the sex appeal of driving F1 cars for a living, and a license to stay out late because they don’t work Sundays.

I was in the cave-like booth of a Singapore nightclub in the wee small hours of a Sunday morning when a ‘third driver’ stumbled in drunk, tripped and landed on a table of 20 champagne flutes. God knows how he explained all the cuts to his physiotherapist.

F1 still knows how to let its hair down, but it’s also a proper job for these guys. The public wants to see heroes who live fast on and off the track. They still do, it’s just you rarely get to read about it.

Less than James Hunt, though I accept that’s a high bar.